I am 2.5% Neanderthal.

That's according to a genetic analysis of snippets of my DNA. It is slightly less than the European average of 2.7%.

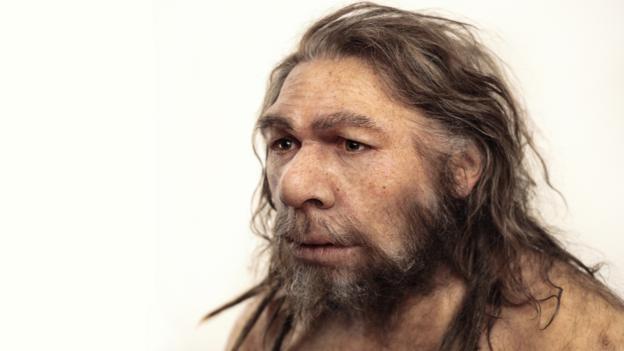

I owe my part-Neanderthal nature to an accident of history. Thousands of years ago, modern humans ran into Neanderthals somewhere in Asia or Europe.

We don't know exactly what happened, but one way or another my ancestors had sex with members of another species. Quite possibly yours did too. We can see traces of these prehistoric trysts in the DNA of everyone outside of Africa – and to a lesser extent, some people in Africa as well.

We now have a rough idea of which of our genes came from the Neanderthals. That offers some surprising clues as to what the Neanderthal DNA is doing for us – and it's not all good.

The announcement that many of us have Neanderthal ancestryhit the headlines in 2010. The finding came as a surprise to many scientists.

"I knew it was a possibility that Neanderthals had mixed with modern humans, but was really biased against it," says Svante Pääbo of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany. "But the strength of genetic data is that once the results are in, one has to believe the results."

The fragments I carry may not be the same ones that you carry

In a pioneering new method, Pääbo and his colleagues fished out ancient DNA fragments from the remains of three Neanderthals found in Vindija Cave in Croatia. These Neanderthals lived between 38,000 and 44,000 years ago. The team then compared their DNA to that of modern humans.

It was the first draft sequence of the Neanderthal genome, and it provided strong evidence that they had contributed to the genes of modern Eurasians. In other words, one of my ancestors not only got it on with a different species, they produced fertile offspring. We now know this happened more than once.

What's more, the amount of Neanderthal DNA in Eurasians ranges from 1-4%. That means the fragments I carry may not be the same ones that you carry.

We recovered sequences from the entire history of interactions that happened between modern humans and Neanderthals

In 2013 scientists sequenced the first high-quality Neanderthal genome. It came from a female discovered in a cave in Siberia, known as the Altai Neanderthal. This complete genome allowed for far more detailed comparisons.

Using it, researchers discovered that 20% of the Neanderthal genome can be found in humans today. No one has all 20%: it is spread across various populations. There could well be more, in other populations not yet studied.

If we sequenced the genome of every living person, we might recover 30-40% of the Neanderthal genome, says co-authorJoshua Akey of the University of Washington in Seattle, US. "The key point is, our study was not just from a single Neanderthal ancestor. We recovered sequences from the entire history of interactions that happened between modern humans and Neanderthals."

Because the Neanderthal DNA is scattered, we don't know much about what it is doing in any one individual. So my 2.5% doesn't mean all that much to me.

But if we combine all our Neanderthal leftovers, we can start to see patterns, and that tells us what we can thank them for.

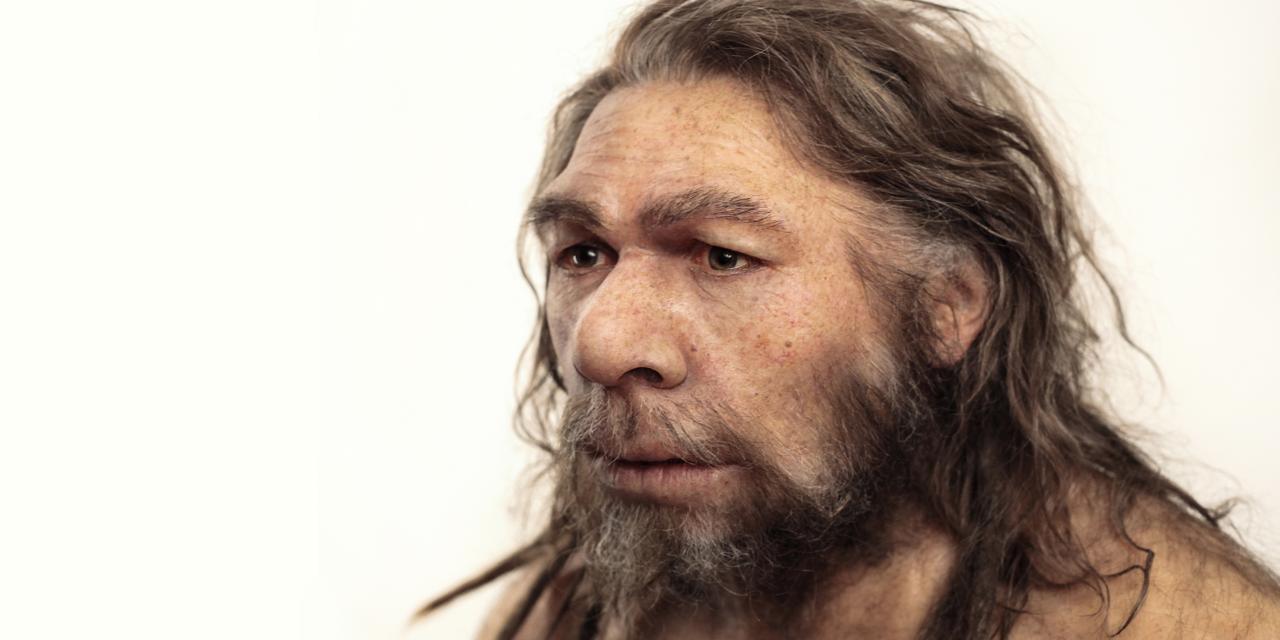

First, some aspects of our looks can be traced to our inter-species frolics.

When researchers combed through the Altai genome and compared it to over 1,000 modern humans, they noticed that some genetic sequences popped up frequently. Rather than being dotted around our genome, Neanderthal DNA is more prevalent in certain places.

Some of our Neanderthal gene variants may predispose us to a collection of diseases and behaviours

For example, almost 80% of Eurasians have Neanderthal versions of the genes that create keratin filaments, says Pääbo.

Keratin is a protein used to strengthen our skin, hair and nails. We may have inherited so much because it could have helped toughen our skin as we adapted to the colder European environment.

It might also have helped us control how much moisture we lose through sweat, says Akey. The trouble is, our skin is our biggest organ and performs a lot of functions, so it's hard to say exactly what advantage these excess keratin genes gave us.

Pääbo thinks this aspect of our inheritance might actually be "rather trivial." But the same studies revealed other Neanderthal genes that might be more significant.

Some of our Neanderthal gene variants may predispose us to a collection of diseases and behaviours. These include lupus, Crohn's disease, type 2 diabetes and depression.

Strangely, some of us also inherited a gene linked to our propensity to get hooked on smoking. I don't smoke, but the genetic test I took told me that, based on my genotype, if I was a smoker I probably smoked more than the average European.

Fiery locks?

Red hair may have been common among Neanderthals, according to a 2007 analysis of Neanderthal DNAled by Carles Lalueza-Fox of Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona, Spain.

However, this does not mean that modern humans with red hair have inherited it from Neanderthals. The genetic mutation that gave Neanderthals their fiery locks cannot be found in modern humans.

Nowadays, people with red hair do have a mutation in the same gene,MCR1, but it's a different mutation.

What's more, the Altai Neanderthaldid not have the red-haired mutation. This hints that, just like us, Neanderthals had more than one hair colour.

It's conceivable that this predisposition to heavy smoking was passed down to me from a Neanderthal. But I don't have enough details to know this for sure.

The same is true of all the purported links with diseases. For example, many genetic mutations are linked to an increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes. We only inherited one such mutation from Neanderthals.

"We have an incomplete understanding of the genetic architecture of most diseases," says Akey. "For any individual, the few per cent Neanderthal genes you carry has a fairly minor impact on the risk of diseases." Most of us therefore have no reason to blame Neanderthals for our illnesses.

If you pool them together, the Neanderthal gene variants have probably contributed to a significant group of genes that influence disease. But even if you had these risky genes, it does not mean you will get the associated disease. "It depends on your genetic constitution and the environment," says Pääbo.

It may seem strange that we inherited disease-causing genes at all. After all, only beneficial genes should survive, so surely over hundreds of generations we should have shaken off these unwanted contributions?

Not necessarily. For one thing, the genes may once have been beneficial.

When we were hunter-gatherers, it was normal practice to go for days without eating

Consider the gene variants that contribute to the prevalence of type 2 diabetes in Western societies, where people rarely go hungry. Those same variants might be advantageous in times of starvation, says Pääbo."It may be some Neanderthal adaptation to starvation that was then picked up in modern humans."

When we were hunter-gatherers, it was normal practice to go for days without eating, says Carles Lalueza-Fox of Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona, Spain. "When you suddenly catch prey, then you sit there and eat for days until it is finished and only the skeleton is left."

That means our genes must have evolved to cope with numerous bouts of near-starvation and occasional days when food was plentiful. If that's true, it is no surprise that Neanderthal genes have now taken a darker turn. We didn't evolve to gorge on food every day, which is why these same genes can cause havoc.

It's harder to explain the gene that makes us prone to tobacco addiction. Not only were there no cigarettes, tobacco is native to North America and nobody lived there during Neanderthal times.

Evolution takes a long time to play out

However, the mutation could have had another function in the past, perhaps relating to the brain receptors that sense nicotine.

Or it could simply be a fluke. "Evolution takes a long time to play out," says Akey. The Neanderthal-human sex happened just over 1,000 generations ago, which is hardly any time. "Sometimes things just happen to stick around. It might look different a million years from now."

Fortunately, it's not all bad news. As well as our keratin-enriched sequences, we also seem to have inherited some genes that boost our immune systems.

When modern humans left Africa and arrived in Europe, they would have encountered all sorts of unfamiliar diseases that they had no immunity to. However, Neanderthals had been in Europe over a hundred thousand years, so they had probably adapted to the local diseases. The offspring of humans and Neanderthals would have inherited some of these adaptations, helping them survive.

For now it is difficult to pinpoint what my 2.5% Neanderthal DNA does. The reason is simple: our understanding of genetics remains limited. Humans have over 25,000 genes, and we have no idea what most of them do.

The problem is made trickier because different people carry different bits of Neanderthal DNA. There may not be any cases where "a single Neanderthal gene is so great that all modern humans today would carry it," says Jean-Jacques Hublin, also of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

It's like a spot on your shirt saying something about 50,000 years ago

Hublin thinks "great Neanderthal genes" do not exist, and that their contribution to our genome is inconsequential. Instead, modern human genes have completely swamped theirs. "It's like a spot on your shirt saying something about 50,000 years ago."

Akey disagrees. He says that, when you look at how much Neanderthal DNA exists around the world, it's clear they have have made a small but significant contribution to "a pool of genes that influence disease".

The Neanderthal DNA is also a guide to what makes our species unique. By pinpointing the places where it is absent, we can identify genes that only our species has developed, says Akey. Those genes might help us understand why we survived, while Neanderthals and every other hominin species died out.

As I write this, geneticists in several labs are busy trying to figure out how influential Neanderthal DNA really is. I remain hopeful that soon I'll find out more about what that 2.5% of my DNA does, and how it has contributed to my life.

No comments:

Post a Comment